Jan Berry 101: A Study in Composition — With Bach, Old Ladies, and Bats

By Mark A. Moore

Author of Dead Man’s Curve: The Rock ‘n’ Roll Life of Jan Berry

Between 1958 and the beginning of 1963, Jan Berry’s talents blossomed as a songwriter, arranger, and producer. During that period, Jan (with successive partners Arnie Ginsburg and Dean Torrence) scored two Top 10 hits, one Top 30 single, and seven additional chart records in the Top 100. There had also been two albums featuring six original compositions co-authored by Berry (in addition to the sides he co-wrote for Jan & Arnie).

By the end of 1962, Jan had fully taken over the reins from producer Lou Adler. “Early on,” recalls Lou, “it was evident that at some point Jan was going to be able to produce himself. On the early Jan & Dean records, a lot of the parts were done by Jan. And so when that first happened I continued to produce, and then I just sort of started to supervise, and then I started to consult. And it just evolved into that.” Jan was 21 years old; and from that point forward he assumed full control in the studio (as well as control over the creative direction for the act).

Along the way, Jan had also honed his skills at reading and writing music notation. He had taken piano lessons as a kid, but by the time he was a teenager, Jan had gotten serious about music. Jan’s garage band, the Barons, experimented with multi-part vocal harmonies years before Jan ever met Brian Wilson; and Jan and future Beach Boy Bruce Johnston would often play piano at Bruce’s house before heading off to class at Uni High. As a college student in the “pre med” curriculum at UCLA, Jan took courses in music theory, including separate classes in harmony and musicianship. He also spent a lot of time with his nose in a music text called The Professional Arranger-Composer, by Russell Garcia.

By the summer of 1963, Jan had signed three separate contracts with Don Kirshner and Screen Gems, Inc. Jan was signed to the company as a songwriter, as a record producer, and as the artist Jan & Dean. The previous spring, Screen Gems had assumed complete control of the Jan & Dean enterprise from its predecessor, Nevins-Kirshner; and Screen Gems signed a new contract with Liberty Records (the duo’s label) to release and distribute Jan & Dean material. Thanks to specific clauses in his contracts, Jan was given full label credit as both an arranger and producer—not only for Jan & Dean but for outside artists he produced, as well.

In a one-year span between the summers of 1963 and 1964, Jan & Dean scored five Top 10 blockbusters in a row (as charted by Cash Box and Billboard), on the way to cementing a pioneering place in the pantheon of the West Coast Sound. Between early ’63 and the summer of ’64, the legendary creative relationship between Jan Berry and Brian Wilson had flourished. Jan and Brian were powerful catalysts for one another—each boosting aspects of the other’s creative and studio abilities. Jan was impressed with Brian’s melodies and harmony structures; and Jan (having been in the music business for five years before he started working creatively with Brian) had a direct impact on Wilson’s growth as a record producer. “He was a great producer,” remembers Brian of Jan. “He knew how to produce records very well. I learned to make cleaner backing tracks from Jan.” Brian also admired the way Jan could sing bass parts like Mike Love, and he admired Jan’s talents on piano. “I learned something from him,” continues Brian. “I learned to be ambitious from Jan . . . He had a very strong spirit for recording music.”

Jan BerryJan’s talents in the studio had matured through a steady evolution (always in tandem with his other life as a college student). Aside from the two chart-busters on the Surf City album (the title track and “Honolulu Lulu”), Jan & Dean didn’t really hit their stride until Drag City (their fifth album overall, released in November 1963, and the third album produced by Berry). With a strong theme of cars and girls (as opposed to cities), Drag City was an album of firsts for Jan & Dean. It was the first to include a majority of original compositions written by Jan and various combinations of his core creative team, which at that time included Brian Wilson, Roger Christian, and Artie Kornfeld. It was also the first album to introduce the overt comedic angle for certain Jan & Dean songs. Lastly, Drag City was the first to offer a full album’s worth of cuts featuring the depth and quality of arrangement and production for which Jan Berry became well known—both vocally and instrumentally. “Dead Man’s Curve” was the only obvious “rush job” (and that cut was soon re-worked into blockbuster status).

Drag City set the tone for the three albums that followed in 1964: Dead Man’s Curve/The New Girl In School (#42, #80), Ride the Wild Surf (#26, #66), and The Little Old Lady from Pasadena (#40, #40). In addition to various Top-10 and Top-40 hit singles, each of these releases featured stellar album cuts (including several nice instrumentals co-written by Jan). Drag City did win the chart battle, however, rating as Jan & Dean’s highest ranking album at #17 on Cash Box and #22 on Billboard.

A STUDY IN BACH — Arrangement Proper and Production Prim

By the summer of 1964, Jan’s arranging and producing skills had reached a new level of sophistication. Though he’d been admitted to the California College of Medicine in September 1963, Jan’s interest in music had taken him back to UCLA for a second summer session, where he was enrolled in a class on late-Baroque-era composer J. S. Bach. Of his initial idea for the intricate musical composition that emerged from that course, Jan said simply: “I got it out of a book” (meaning a music text). Jan & Dean were at their peak in that final summer of Surf. “The Little Old Lady (from Pasadena)” — with music by Jan Berry and lyrics from Don Altfeld and Roger Christian — was burning her way up to #3 on the national charts (just as “I Get Around” by the Beach Boys was descending from the top spot). But thanks in part to J. S. Bach, this new composition would take the Little Old Lady shtick to greater heights of musical complexity—both instrumentally and vocally.

The song inspired by Jan’s class was “The Anaheim, Azusa & Cucamonga Sewing Circle, Book Review, and Timing Association.” (We’ll call it “Anaheim” for short). Once again, Jan wrote all of the music and arrangements, with lyrics from Don and Roger. Jan based his composition on a traditional German Christmas song called “Lobt Gott, ihr Christen, allzugleich” — a chorale that Bach had harmonized in several different formats. The similarities are evident in the opening and ending of “Anaheim,” but Jan’s entire piece had a classical feel with exotic instrumentation.

As he did with almost every Jan & Dean record, Jan notated (scored) all of the individual musical parts he wrote for “Anaheim.” His personalized, pre-printed orchestral score sheets heralded “A Jan Arrangement” in cursive script across the bottom. He scored in pencil, so the parts could be modified easily if he changed his mind about anything.

Jan notated the instrumental parts for “Anaheim” in a neutral key (an approach he didn’t always use). The horn and woodwind section featured parts for oboe, trumpet, French horn, and bassoon (scored in that order). These parts harmonized in a classical structure (along with the vocals) during the song’s powerful opening, which flowed between 4/4 and 2/4 time signatures. These four instrumental lines also blended to underpin the tune in the verse and chorus, bursting through with key portions of the melody between breaks in the vocals.

There were three separate guitar parts on “Anaheim.” The first was written for standard guitar. The second was written for an exotic axe known as a Danelectro “Bellzouki” 12-string. The Bellzouki (popularized by guitarist Vinnie Bell) had a dry, distinctive sound with immediate decay — a cross between a guitar and mandolin. The third guitar part was written for a Danelectro 6-string bass. Jan notated this part in the treble clef (as opposed to bass clef). For the standard guitar and Bellzouki, Jan wrote a combination of standard notation, rhythmic notation, and slash notation with chord progressions. For the bars with slashes, Jan would write little instructions to the players (the same elite studio cats he always used for his sessions, including Billy Strange and Tommy Tedesco). For “Anaheim” that instruction was “Jan & Dean Usual,” which was the guitarists’ cue to incorporate the various elements that had become commonplace on Jan’s tracks — a combination of strummed chords and double-stop grooves, spiced with occasional eighth or sixteenth note licks, inserted in the right places. These parts can be heard to good effect on the instrumental track for “Anaheim.” Otherwise, the guitarists played the specific notes Jan provided. (Copyists generated all individual parts for the musicians from Jan’s original handwritten scores).

The standard bass part was written for two players, with instructions for a Fender to take the “top notes” when not in unison. Drums (Hal Blaine and Earl Palmer) and piano rounded out the rhythm section. There were various auxiliary percussion parts, including bells; and Leon Russell played “tack piano” (whereby metal tacks in the hammers provided a bright and brassy sound). But the ultimate embellishment came with the harpsichord groove that rolled between the lead vocal and staccato rhythm kicks in the verse (one of the last parts added to the track on August 11, 1964).

Aside from this construction, which was used for the record, Jan also wrote an even more elaborate alternate arrangement with different instrumentation. This second version featured five separate woodwind parts, three trumpet parts, and three trombone parts.

The vocal harmonies on “Anaheim” were a four-part structure with falsetto, and flowed atop the horns and woodwinds in the opening (and refrain). The vocals were scored in the key of E (as opposed to neutral C). Jan sang bass, with Dean Torrence, Phil Sloan, and Steve Barri handling the middle and high parts. Jan wrote each of their names on the staves for their respective parts. Dean’s name was on the falsetto line, but it was Phil Sloan (“Flip”) who ended up providing the soaring falsetto voice throughout the song. “Jan had it all mapped out,” says Phil of a typical vocal-learning session. “We would sit down at the piano, and he would play our parts for us, and teach them to us individually. Even the falsettos.” “Exactly,” agrees Steve Barri. “He would give everybody their parts. And then when we would actually record, Jan would sit at the piano and hit his notes so that he could hear them; and then we would stand at a microphone nearby.”

Jan pushed Sloan and Barri hard to get the vocals right on “Anaheim.” Phil’s memories are vivid: “Steve Barri and myself spent uncounted hours . . . learning and recording the parts. It took days. Like actors in a scene we grew to love the song, and then to like it, and then finally to dislike it—due to the immense number of takes and hours it took to do each section of the song. In those days you didn’t record one part and then splice it in wherever you wanted it to appear again.” Reflecting on those long and difficult sessions for “Anaheim”(after 40 years), Phil jokes: “Listening to it now, it doesn’t sound that complex anymore . . . [but] it’s still an enjoyable recording to me.”

As usual, Jan was at odds with Liberty over the budget (and everything else). Jan wanted things done his way, and he didn’t care about inconveniencing the label with over-costs or odd hours in the studio. His time was at a premium (remember school), and Jan recorded on his own schedule, regardless (often in the middle of the night). Recording engineers Bones Howe and Lanky Linstrot both have vivid memories of Jan’s total disregard for running up the bill. It was par for the course. On “Anaheim” specifically, Phil Sloan continues: “Jan was very proud of this song and his arrangement of it [but] the record company didn’t like it much, and felt he had gone overboard . . . They felt that way every time he asked for the money to use a flugelhorn or harp.” Indeed, Jan & Dean’s royalties were docked to cover the 85-dollar rental fee for the harpsichord at the August 11 session. It wouldn’t be the first time, and certainly not the last. But any amount of money lost was a small price to pay, in Jan’s view, as long as the record came out exactly as he envisioned it. By this point in his career, Jan Berry had a permanent one-finger salute for both Screen Gems and Liberty.

“Anaheim” was released as the B-side of “Ride the Wild Surf” in late August 1964 (and was also included on the Top-40 Little Old Lady LP released in September). The A-side reached #16 on the charts, while “Anaheim” made a brief appearance in the Top 100 (#50, #77). Nevertheless, “Anaheim” remains the ultimate Jan & Dean track—one of Jan’s most complex and pleasing productions. It had all of the hooks associated with the Jan & Dean sound, but it took them to a new level. Above all, the song featured the classic dichotomy of Jan & Dean—a “Schlock Symphony”—featuring an intricate musical arrangement coupled (in this case) with comedic shtick about a rowdy bunch of senior citizen hot-rod fanatics. To quote Dave Marsh: “Heavy stuff, that.” More importantly, “Anaheim” was a look toward the future—illustrating that Jan Berry was writing arrangements inspired by classical music nearly a year before he began work on Pop Symphony (his prized orchestral collaboration with George Tipton the following spring).

A STUDY IN BAT — Holy Instrumentation

The year 1965 brought a change in sound for Jan & Dean. Gone were the days of long-boards and cherry rods. That fall, Jan admonished a reporter: “There is no real ‘surf music,’ or ‘surf sound.’ There is just the ‘sound’ of the individual artists. We don’t have a ‘surf sound’.” There was also a departure from comedy (at least on vinyl) with Pop Symphony, various album cuts, and two Top-30 singles, “You Really Know How To Hurt a Guy” and “I Found a Girl.” Additional LPs with new material that year included Command Performance (“live” with previous hits and covers) and Folk ‘n Roll. But by late in the year, and into early 1966, Jan & Dean were working on projects that would bring the comedy angle to the forefront—in a cutting-edge way.

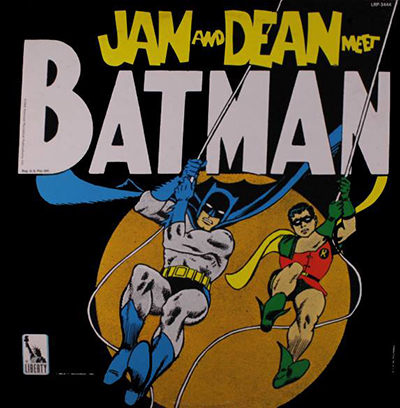

With the appearance of the campy new Batman television series, it was only natural that Jan & Dean would find a way to put their own ingenious spin on the Caped Crusaders—Batman and Robin. Or as it turned out, Captain Jan . . . and Dean, the Boy Blunder. The resulting chart single was another masterpiece of arrangement and production from Jan Berry, and the comedy concept album that followed was ahead of its time.

The music and arrangement for the “Batman” single (released in January 1966) were written by Jan, with lyrics from Don Altfeld and Fred Wieder. Jan scored the song in the key of C, with transposing instruments such as trumpet, French horn, and alto sax written in their respective keys. Structurally, “Batman” is similar to the arrangement for “Anaheim,” but it makes use of diminished chords in the opening and bridge, which segue from 2/4 to 4/4 time signatures. Indeed, there are time signature changes throughout the song. There are also various minor, 7th and 9th chords interspersed throughout, with a key change to D flat late in the piece (Jan was fond of key changes).

Instrumentally, “Batman” featured a brass and woodwind section with two separate trumpet parts, two trombone parts, French horn, and alto saxophone. There were three guitar parts (the “inside” instruction for the rhythm slashes this time was “J&D Shtick”), as well as parts for bass, drums, timpani, and piano. To fill out the lower end, Jan wrote a tuba part to double the bass line (Holy resonance). Once again the vocal harmonies were four-part, with falsetto from Dean Torrence.

Lyrically, the tune declared that Batman & Robin were on the scene to “keep evil at bay,” ready for battle with familiar villains such as the Riddler, Penguin, and Joker. I must be a creature of the night! Sound effects on the record included the Joker’s laugh and the Batmobile peeling out. (The comedy skits on the album, Jan & Dean Meet Batman, took a different approach with “Captain Jan” and “Dean, the Boy Blunder”—but that’s a story for another time).

The most ingenious aspect of Jan’s “Batman” arrangement, however, was the way he incorporated a variation of Neal Hefti’s famous guitar groove from the instrumental Batman theme. Woven seamlessly into the song, it occurs between the lead lines in the verse, and in the chorus. Guitar alone might have been effective; but Jan took it to its deepest level. As the backing vocals declare “Gotham City, here they come,” Jan’s adaptation of Hefti’s theme occurs with at least ten different instrumental voices playing a multi-tonal variation—all at the same time. A similar variation happens in the chorus. We need the Batman! Composer Cameron Michael Parkes observes: “‘Batman’ is one of Jan’s most sophisticated scores. Harmonically very complex . . . very clean and surprisingly economical.” The song peaked at #60 on Cash Box and #66 on Billboard.

As with all of his scores, “Anaheim” and “Batman” reflect Jan’s attention to detail. Expressions, articulations (symbols explaining how particular notes should be played), and dynamic markings are all carefully placed. In many cases, the finished individual charts also bear Jan’s editorial scribbles and alterations; and Jan would consult frequently with fellow arrangers, such as George Tipton.

Most importantly, Jan’s arrangements for “Anaheim” and “Batman” confirm that some of Jan & Dean’s finest recordings were not always major hit singles. In some cases, the lesser singles, album cuts, and B-sides were as good or better. But why all of this semi-technical discussion about time and key signatures, instrumentation, dynamics, and vocals? Because that’s the level on which Jan Berry wrote and worked with his arrangements. That’s who he was. At the same time, it’s true that Jan—a mischievous joker from day one—embraced and relished the slapstick humor that he and Dean Torrence presented to the public. It was reflected in many of their records; and Jan remained a steadfast Laurel & Hardy freak until the day he died. When I first walked into Jan’s bedroom in L.A. after he’d passed away, who do you think I saw sitting atop the little velvet-covered box containing Jan’s ashes? It was Stan Laurel, grinning sheepishly, accompanied by a smirking Oliver Hardy—two of Jan’s favorite puppets from his extensive Laurel & Hardy collection. (Now friends and neighbors, how fitting was that? Jan’s probably still laughing his eternal ass off over that one.)

But musically speaking, the studio and the nuts and bolts of his compositions were always Jan’s first love. You can’t get any closer to Jan than to dissect his personal charts and scores. They were his passion—the origins of everything you hear on Jan & Dean records. As a detail-oriented arranger and producer, Jan was all about the notes on paper, and how best to achieve the sound he wanted from the various musicians, vocalists, and engineers at his disposal — and to hell with anyone or anything that got in his way. Is it any wonder that Jan Berry and Brian Wilson knocked each other out, on a mutual level?

© 2004 Mark A. Moore. All rights reserved.

Originally Published in Endless Summer Quarterly (Summer 2004)

Just an amazing website that I’m glad I took the time to read and explore.Jan + Dean were always in my top four groups of all time ( Stones,The Who,The Beach Boys) the other three.I have been fortunate enough in my fifty eight years of life to have seen these four acts LIVE.The Jan + Dean shows were in July of 1985 and again July of 1996 in Toronto,Canada at the ‘ Revolving Stage’ of Ontario Place.Needless to say I was not disappointed at either show and had Jan autograph an album cover for me afterwards.(Greatest Hits Volume One-Gold Cover) .Aside from the music what struck me was how so many youngsters of the time seemed to know every song word for word.They were probably my two favourite concerts of all time and I’ve seen Jagger and company ten times.I was awestruck at the fact when ‘Deadman’s Curve’ hit Jan’s speaking part in the middle you could’ve heard a child cough miles away.That’s how good this show was,everyone was taken in one hundred percent..!!